Casey Miller (1919-1997)

Kate Swift (1923-2011)

They Started a Movement to End Gender Bias in the English Language

Through their writing, they helped change language and promote gender equity

By ALEX GERRISH

Casey Miller (1919-1997) and Kate Swift (1923-2011) were outspoken advocates for eradicating gender bias in the English language. Over their 30-year partnership, working from their Main St. home in East Haddam, they published numerous articles and two groundbreaking books that identified sexist language and its impact on writing and society.

Before East Haddam

Casey Miller was born on February 26, 1919, in Toledo, Ohio, and earned a degree in philosophy from Smith College. She went on to serve as a lieutenant in the US Navy during World War II, working in Washington, D.C. to break Japanese codes. In 1967, she moved to East Haddam to work as a freelance editor and writer.

Kate Swift was born on December 9, 1923, in Yonkers, New York. She graduated from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1944 with a degree in journalism. Swift served two years in the US Army and worked as an information and education specialist until being honorably discharged with the rank of sergeant. Both Miller and Swift held numerous jobs and lived in varying places before crossing paths in Connecticut and forming their partnership.

Casey Miller (left) and Kate Swift lived on East Haddam's Main St. for more than 30 years. Through their trailblazing articles and books, they inspired a language makeover. They are pictured in the 1970s at the summer cottage they built on Bay Point in Georgetown, ME. Photo courtesy of the Swift family.

The Beginning of a Journey

Miller and Swift’s working relationship began in 1970 when they were editors of a sex education handbook for high schoolers. Despite an audience of all high schoolers, the author wrote the handbook from a male point of view and only used male pronouns—he, him, his, etc.—alienating female readers. This realization alarmed both Miller and Swift and they soon began finding other examples of sexism in popular texts. From then on, both women devoted their careers to raising awareness about sexist language.

In this 2004 interview at her East Haddam home, Kate Swift talked about her career, her relationship with Casey Miller and how they uncovered sexism in language and wrote about it. Scroll down to see the rest of the interview.

While editing the handbook, Miller and Swift had no intentions of writing a separate book of their own. Per the advice of their publisher, however, they mentioned a book project in their author biography. As the handbook gained popularity, readers began asking about the book project to which they alluded. This interest encouraged Miller and Swift to publish Words and Women in 1976.

Rewriting the Norm

Miller and Swift’s research had a significant impact on linguistics and the power of language. In particular, Words and Women outlined how popular media assumed most “genderless” characters to be male.

Miller and Swift wrote, “The linguistic presumption of maleness is reinforced by the large number of male characters, whether they are human beings or humanized animals, in children’s school books, storybooks, television programs, and comic strips…In short, the male is the norm, and the assumption that all creatures are male unless they are known to be female is a natural one for children to make.”

Casey Miller (left) and Kate Swift with their beloved pet Sadie. Longtime residents remember them regularly walking Sadie from their East Haddam Main Street house to the nearby Rathbun Library using a clothesline for a long leash.

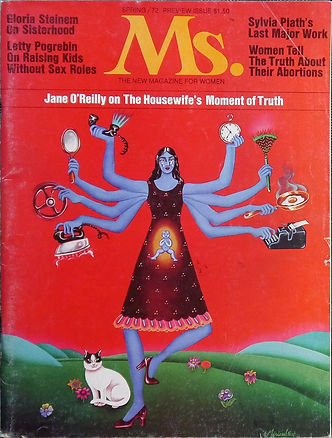

The Spring 1972 preview Issue of Ms. included "Desexing the English Language," the first published article about sexist language by Miller and Swift.

Their assertions proved controversial. For example, many people believed that words such as “firemen” included everyone, despite the male oriented suffix. A large part of Miller and Swift’s mission, however, was not just to outline the problem, but to convince others to help fight against the stereotype.

The authors argued that gender bias is revealed in the way writers and others use language. Using the changing demographics of teachers as an example, they wrote, “Until a few years ago most publications, writers, and speakers on the subject of primary and secondary education used ‘she’ in referring to teachers. As the proportion of men in the profession increased, so did their annoyance with the generic use of feminine-gender pronouns.” If men did not want to be grouped with female-oriented language, why should women be okay with being grouped with male-oriented language?

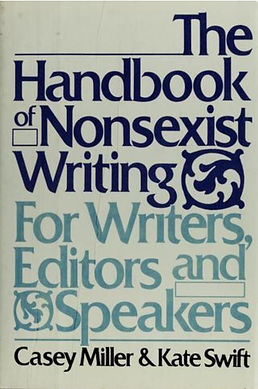

After Miller and Swift’s first book, readers became increasingly open to communicating in a more inclusive, less male-oriented way. As a result, Miller and Swift published their second book, The Handbook of Nonsexist Writing, in 1980.

In 1971, "The New York Times Magazine" editor Victor Navasky assigned an article on sexism in language to Ms. magazine founding editor Gloria Steinem. She put him off for a year and finally suggested that Casey Miller and Kate Swift could write it — and deliver it soon. Using Steinem's files on the topic and their own research, they wrote "One Small Step for Genkind," published April 16, 1972. That article led to their fwo pioneering books on sexist language. Click for a PDF of "One Small Step for Genkind."

Miller and Swift's groundbreaking books identified sexism in language and how to use non-sexist language in communications of all types. They were first published in 1976 (left) and 1980. Second editions were printed in the 1990s.

Along with their books, Miller and Swift continued to promote inclusion through speeches and articles in prominent publications such as Ms. magazine. The literary world further celebrated Miller and Swift by inviting them to speak at the Conference on Language and Style and many others. In addition, the authors championed social causes such as marriage equality, abortion rights, and more.

Miller and Swift worked closely together as business partners and dear friends for the remainder of their lives. Their work not only opened doors for women but also began conversations on the power and adaptability of language that continue to this day.

East Haddam resident Alex Gerrish is the Programs Manager at the Noah Webster House and holds a B.A. in American Studies from Western New England University. This article first appeared in ConnecticutHistory.org, the online resource of state history.

Kate Swift on Her Life, Her Loves, and Linguistic Sexism

In 2004, Kate Swift was interviewed in her East Haddam home about her life, career, and how she and longtime partner Casey Miller became a catalyst for change in the English language. We've re-edited the interview into 12 short videos.

Kate Swift: How It Started

Kate Swift: How Casey and I Met

Kate Swift: Light Bulb Experience

Kate Swift: Tey Ter Tem

Kate Swift: Words and Women

Kate Swift: Writing with Equity

Kate Swift: First Big Book Review

Kate Swift: How It Went

Kate Swift: My Feminist History

Kate Swift: Finding the Grassroots

Kate Swift: My Bisexual Life

Kate Swift: Casey and Me

Life in Hastings-on-Hudson, Bay Point, and East Haddam

Kate Swift had always assumed as a child that she'd be a journalist like her parents. She started early, publishing a mimeographed weekly at the age of 11. Her first job after college in 1944 was as an NBC "copy boy." After a series of positions and assignments in press and public relations, she met up with Casey Miller. They established a professional partnership writing and editing for institutions and publications. When they began writing about sexism in the English language in 1970, it provoked a language revolution. Photos courtesy of the Swift family.